Botox and Muscle

The use of paralytic botulinum toxins in muscles of mastication has vastly expanded in recent years.

In addition to cosmetic facial shaping, these toxins are intended to relieve spasm and reduce pain. However, such treatment removes the major forces applied to the jaw, which like other bones requires loading for maintenance. The functional effects on muscle are temporary, but evidence on structural changes is lacking. In her 2020 presentation Sue Herring centers on a comprehensive series of rabbit studies which reveal severe bone loss in the TMJ and show further that return of muscle force is due to compensation rather than recovery.

The learning objectives are:

1. Understand the mechanism by which botulinum toxins (Botox, Dysport, Xeomin, Myobloc etc.) affect muscle.

2. Explore the time course of functional recovery after single and multiple injections of toxin into the masseter muscle.

3. Learn how botulinum toxin changes the structure of the masseter muscle and how it affects bone in the mandible.

4. Evaluate whether the effects of botulinum toxins are truly temporary.

The following is a transcribed excerpt (video excerpt available here)

Botox is used in joint muscles all the time but we don’t know very much about what happens inside the muscles. We did an animal experiment using rabbits to see what really is going on inside the masseter muscle after it receives injections of botulinum toxin.

The Image shows what a normal rabbit masseter is supposed to look like.

You see a bunch of homogeneous sized muscle fibers packed into a fascial and in between the fascials there’s little strands of collagen.

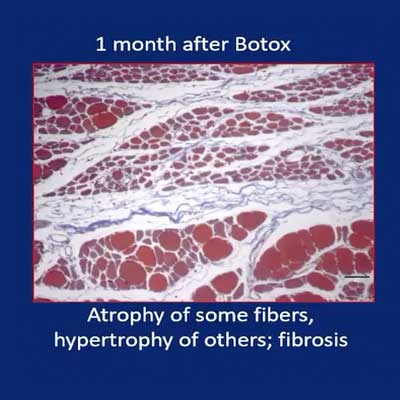

One month after Botox goes in it’s just when muscle activity is beginning to come back in rabbits. As expected, lot of these muscle fibers are atrophied because the treatment paralyzes them. It’s like bed rest muscle fibers just shrink.

Interestingly though some of the muscle fibers are really big. In fact, they’re bigger than normal as if they were not affected by the Botox and they’re compensating for the loss of all these little shrunken ones. You’ll also see a lot more collagen fibers in there. So we’re getting some fibrosis in the muscle.

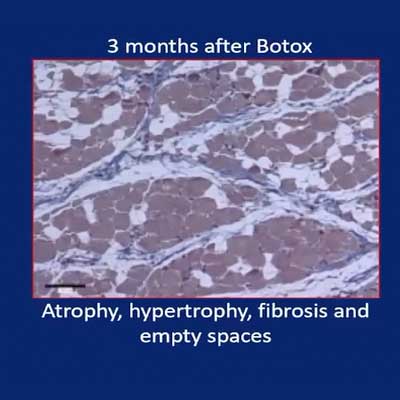

Now, we waited three months because by that time the activities all the way back. Muscles are acting normally and the rabbits are chewing just fine. We thought perhaps the muscle would be completely recovered by this time but actually it turns out that it’s not completely recovered. Some of the fibers apparently have died. There is even more fibrosis than there was before. There’s still some very very small atrophied fibers in them but very many of the fibers are hypertrophy.

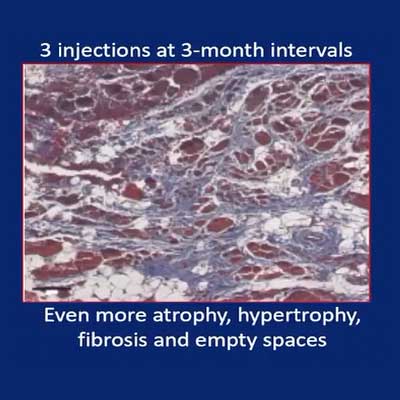

Finally, we had some rabbits in which we injected the Botox three times each one with a three month recovery in between because lots of people get repeated treatments of Botox.

Here we find all the changes have gotten worse. There is more fibrosis, more dead fibers more little teeny atrophied fibers that apparently have never started contracting again. But also a whole bunch of really gigantic ones and these are apparently the ones that are responsible for activity coming back.

Conclusion

These muscles which we’ve denervated

by the Botox aren’t really recovering the fibers that were affected don’t get better but other fibers which are not affected by the botox but which remain functional or they recover very fast from it are compensating for it and that’s what brings the function back.

About Sue Herring

Sue Herring was trained at the University of Chicago (B.S. Zoology, Ph.D. Anatomy) where she studied the comparative cranial anatomy of pigs and their close relatives. Feeling the need to work with live animals, she moved to the College of Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago as an NIH postdoctoral fellow, where she developed techniques to record masticatory muscle activity and jaw movement from unrestrained animals. She remained at UIC until 1990, rising to Professor of Oral Anatomy and Anatomy. In 1990 she took up her current position in Seattle as Professor of Orthodontics and Oral Biology (now Oral Health Sciences) at the University of Washington. Her work on the biology of the craniofacial musculoskeletal system has been continuously funded by NIH for over 35 years. She has served on the editorial boards of multiple journals and held office in several societies, including the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology (chair, Vertebrate Morphology, 1983-4), International Association of Dental Research (Craniofacial Biology Group, president 1997-8), International Society of Vertebrate Morphology (president, 1994-7), and AAAS (member-at-large, Section R, 2008-12). She became a fellow of AAAS in 1992 and of AADR in 2018. She is the recipient of the Craniofacial Biology Research Award from IADR (1999) and the Rothwell Lifetime Achievement Award from UW Dentistry (2015). Her work on the effects of botulinum neurotoxin injection into the muscles of mastication received the Watson Award from the Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. in 2016.